Relativity

Early Hints

Galilean Invariance & Reference Frames

Faraday's Giant Electromagnet

1830's: Michael Faraday was making charges move with coils and magnets.

He experimentally showed that a changing magnetic field will create a current, and the inverse. These phenomena we now call induction.

J. C. Maxwell

1855: Maxwell: "On Faraday's lines of force"

"We can scarcely avoid the conclusion that light consists in the transverse undulations of the same medium which is the cause of electric and magnetic phenomena."

Maxwell, ~1862

The Maxwell Equations

$$ \begin{align*} \nabla \cdot \mathbf {E} & = 4\pi \rho \\ \nabla \cdot \mathbf {B} & = 0 \\ \nabla \times \mathbf {E} & =-{\frac {1}{c}}{\frac {\partial \mathbf {B} }{\partial t}} \\ \nabla \times \mathbf {B} &={\frac {1}{c}}\left(4\pi \mathbf {J} +{\frac {\partial \mathbf {E} }{\partial t}}\right) \end{align*} $$

These were the laws the described the electromagnet phenomena, just like $F = ma$ described mechanical motions.

Invariance

Answer to the question: what do observers in two difference inertial reference frames agree on?

For Newton's Laws: Length!

\begin{equation} \Delta r_{\textrm{Eucl.}}^2 = (x_2-x_1)^2+(y_2-y_1)^2+(z_2-z_1)^2 \geqslant 0 \end{equation}

Distance in Galilean Relativity

Simple Example (in 2d)

Unprimed Frame $$\sqrt{(6-3)^2+(7-2)^2}$$

Primed Frame $$ \sqrt{(1-(-4)^2+(5-2)^2} $$

It was quickly realized that the Maxwell equations did not share the same invariance as Newton's Laws.

This was the first problem.

And if there is a translational invariance, then one could determine whether or not a frame had a velocity.

The second 'problem' grew out of several experiments that showed that light wasn't acting like a 'regular' wave would.

Normally, a mechanical wave would be affected by the motion of the medium it's traveling in. i.e. a water wave in a moving current will take on the velocity of the current as well as its own wave speed.

Such affects were found to be non-existent through several experiments.

Experiments:

- 1851: Fizeau experiment (speed of light in a moving fluid)

- 1887: Michelson–Morley experiment (speed of light depending on which way Earth is moving.)

Lorentz

Notably, in response to experiments, Lorentz and others proposed the following transforms, to be used instead of the Galilean transformations.

Wording: What's a postulate?

Einstein's Postulates:

- The laws of electrodynamics and optics will be valid for all frames of reference for which equations of mechanics hold good.

- Light in a vacuum moves at a speed $c$ which is independent of the state of motion of the emitting body.

Einstein's Paper

Einstein's paper took all these pieces and assembled them into a new understanding of our physical world:

On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies (pdf)

But, 3 years later, an extension on the idea was discussed by Herman Minkowski.

A Blank Space time diagram

A Galilean transformation example

Galilean Transform in Linear Algebra

\begin{equation} {\begin{pmatrix}x'\\t'\end{pmatrix}}={\begin{pmatrix}1&-v\\0&1\end{pmatrix}}{\begin{pmatrix}x\\t\end{pmatrix}} \end{equation}Space Time Diagrams

Construct our moving frame axes

The diagram with the $x'$ and $ct'$ axes in place

An event shown in both frames

Minkowski Invariant

In this new spacetime (as opposed to Euclidian Space), we still can have an invariant quantity:

\begin{equation} -c^2 \Delta t'^2 + \Delta x'^2 + \Delta y'^2 + \Delta z'^2 = -c^2 \Delta t^2 + \Delta x^2 + \Delta y^2 + \Delta z^2 \end{equation} or more simply in 1+1 dimensions: $$ -c^2 \Delta t'^2 + \Delta x'^2 = -c^2 \Delta t^2 + \Delta x^2 $$

These can be shown to be invariant under a Lorentz Transformation

What is invariant ?

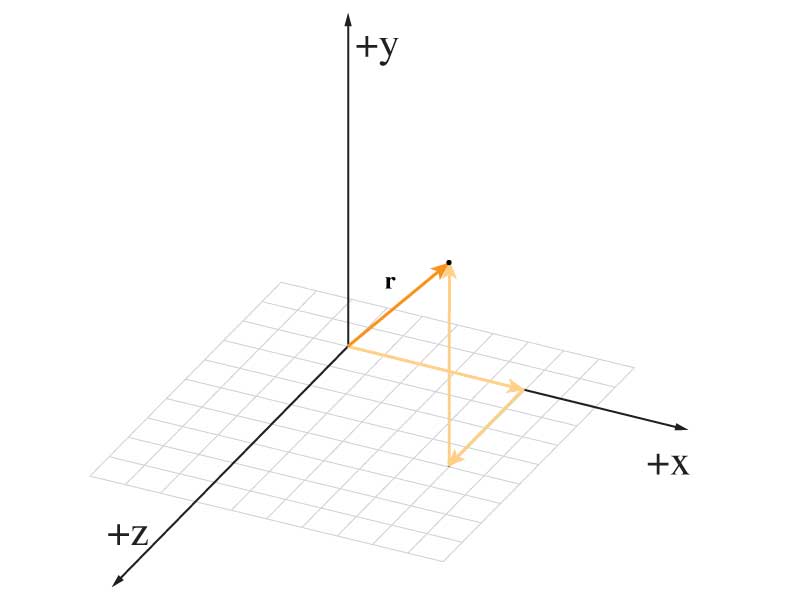

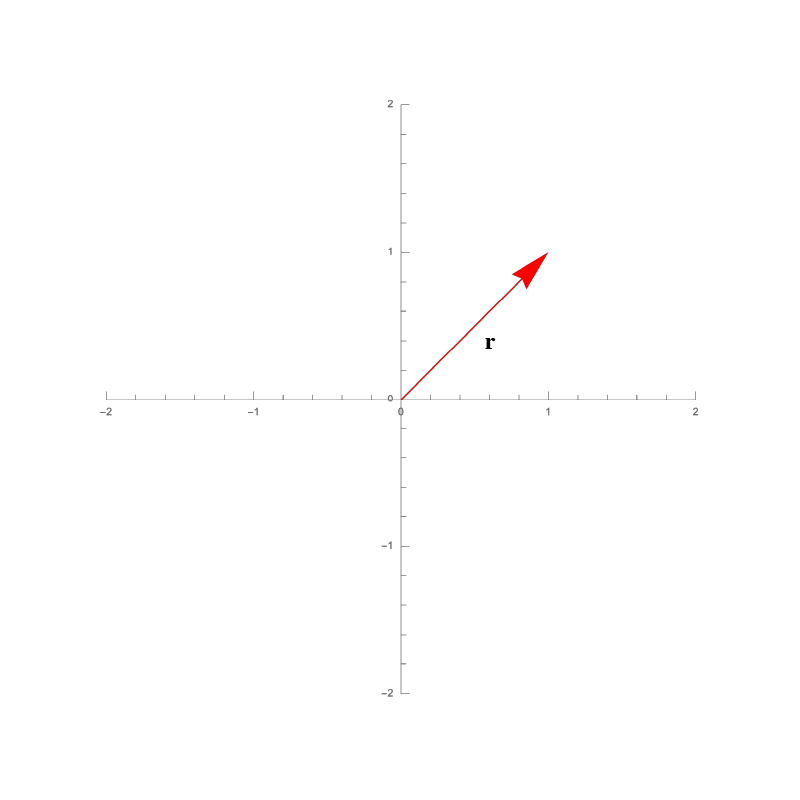

$\mathbb {R} ^{3}$

$\mathbb {R} ^{3}$

Our everday 3d world is known more formally as $$\mathbb {R} ^{3}$$. This is a vector space with 3 real coordinates. We map them onto our human notions of $x,y,z$.

We describe positions using regular vectors: $$\mathbf{r} = \begin{pmatrix} r_x \\ r_y \\ r_z \end{pmatrix} $$

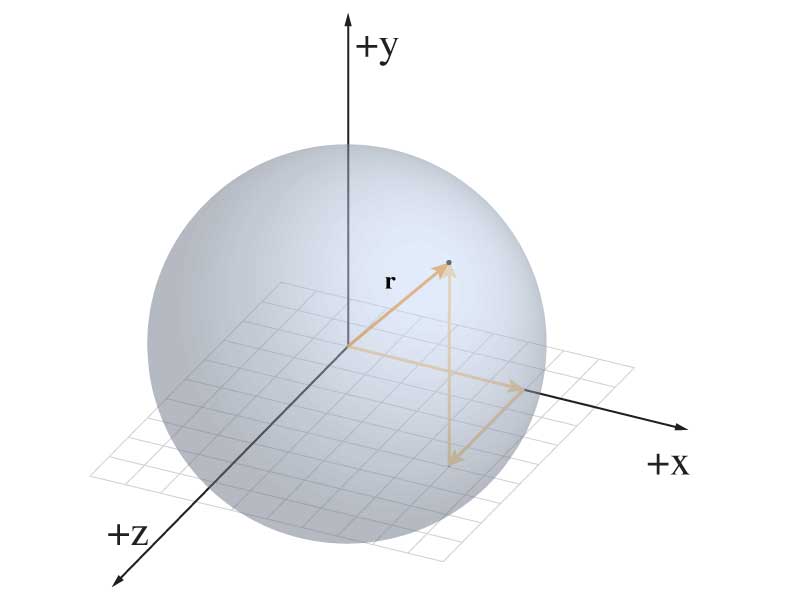

The collection of places where $r^2$ equals $C$

We can express the length of such a vector by the following: \begin{equation} |\mathbf{r}| = \sqrt{r_x^2 + r_y^2 + r_z^2} \end{equation} or, if that was some change in position, then we could just as easily consider: \begin{equation} \mathbf{\Delta r}^2 = \Delta r_x^2 + \Delta r_y^2 + \Delta r_z^2 \end{equation} And using galilan transforms between coordinate systems, everyone would 'agree' that that value of $\Delta \mathbf{r}^2$ remains the same.

Furthermore, we can image the region of space where that quantity is equal to some value: it's a sphere.

in Minkowski 4-space

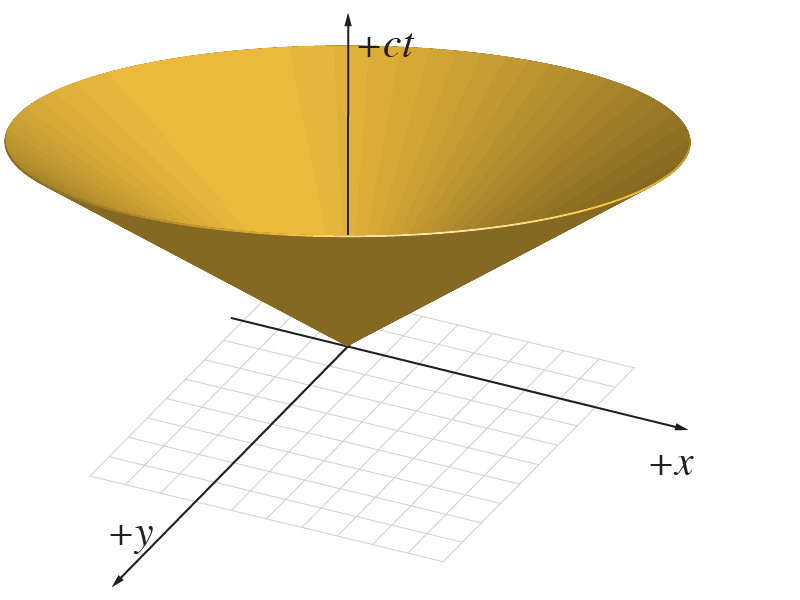

Recall the 2nd postulate - speed of light is the same

Thus, for a photon: $$ c^2 dt^2 = dx^2 + dy^2 + dz^2 $$ Or, if we're just concerned with one dimensional motion: \begin{equation} c^2 dt^2 = dx^2 \end{equation} \begin{equation} -c^2 dt^2 + dx^2 = 0 \end{equation} (And every observer, if they're going with the 2nd postulate would have the same result)

World lines for massless particles moving at speed $c$.

In 1d, we can plot ct(x) and see that we get two lines leading away from the origin at 45° These are the world lines of photons.

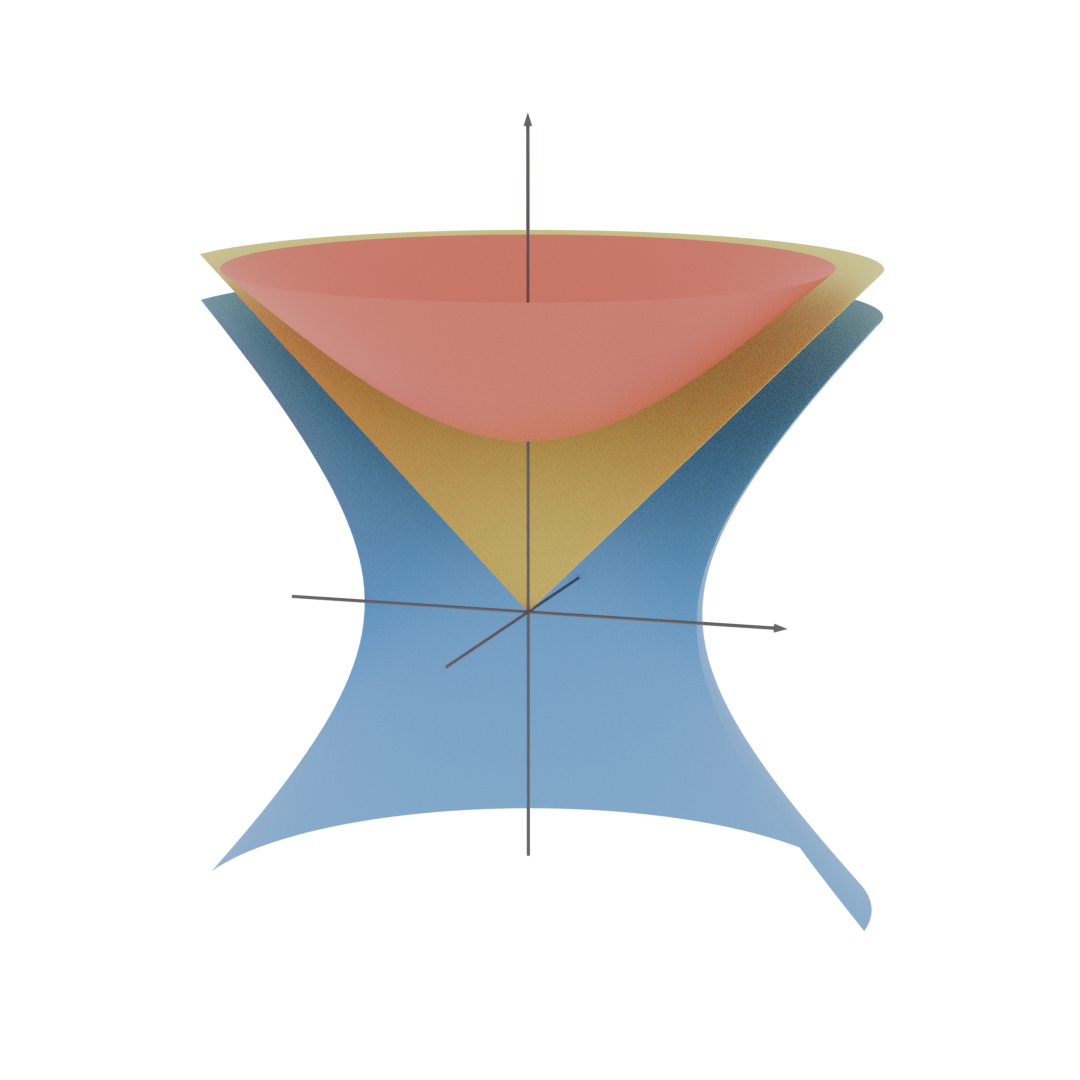

2d light cones

In 2 spatial dimensions, we can see that these lines are really just the edges of a cone – the light cone.

Hence, \begin{equation} ds^2 = -c^2 dt^2 + dx^2 \end{equation} will be our invariant quantity for spacetime.

Now, what if that 'separation' in spacetime $ \neq 0$?

i.e. what if $$ds^2 = -c^2 dt^2 + dx^2 \gt 0$$ or $$ds^2 = -c^2 dt^2 + dx^2 \lt 0$$

The hyperbolas

Let's start with $ds^2 \lt 0$, eg: $$ds^2 = -c^2 dt^2 + dx^2 = -1$$ We can plot these separations using: $$ct = \sqrt{dx^2+1}$$ And all the points along this hyperbola are the same 'spacetime' distance away from us.

These points would all be considered 'time-like' in the separations from the origin.

3 events, a,b, and c

Consider the 3 events shown in the figure.

- A ball in your hand $t$ seconds from now.

- A ball over there $t$ seconds from now.

- A ball over there $>t$ seconds from now.

Which two have the same spacetime separation?

The space-like hyperbola

We can also have $ds^2 \gt 0$, eg: $$ds^2 = -c^2 dt^2 + dx^2 = +1$$ We can plot these separations using: $$ct = \pm \sqrt{dx^2-1}$$ And all the points along this hyperbola are the same 'spacetime' distance away from us.

The space-like hyperbola

Space-like separations: these are events we can have no causal influence over.

Time-like separations: if we can travel fast enough, or send signals of light, then we can causally influence these events.

Light-like: the worlds lines of photons.

Spacetime in 2+1 dimensions.

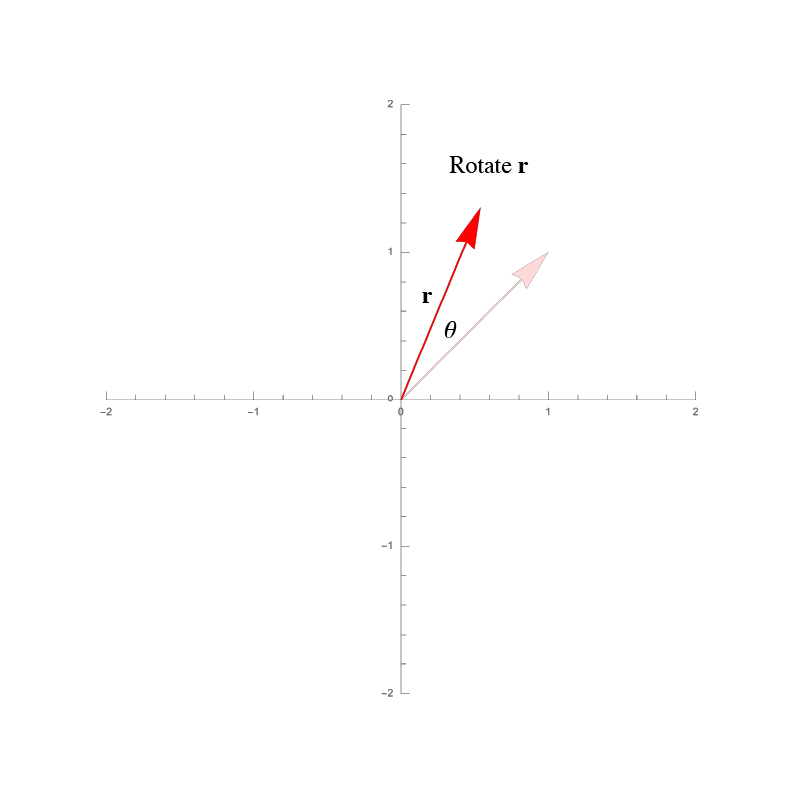

Other Transforms: Rotations

A vector $\mathbf{r}$

Shown is a vector $\mathbf{r}$ $$ \mathbf{r} = \begin{pmatrix} r_x \\ r_y \\ r_z \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} 1 \\ 1 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix}$$ If we wanted to rotate it, we could transform the vector components: $$ \begin{aligned} x & = x' \cos \theta - y' \sin \theta \\ y & = x' \sin \theta + y' \cos \theta \\ z & = z' \end{aligned} $$

A vector $\mathbf{r}$ that has been rotated.

We can express a rotation about an axis as a multiplication of the vector $\mathbf{r}$ with a Rotation Matrix $\mathcal{R}$ $$ \mathcal{R} = \begin{bmatrix}\cos \theta & -\sin \theta & 0 \\ \sin \theta & \cos \theta & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} $$

$$ \mathbf{r} = \begin{pmatrix}\cos \theta & \sin \theta & 0 \\ -\sin \theta & \cos \theta & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 \end{pmatrix} \mathbf{r'} $$

Our Lorentz transformations can also be expressed in a matrix form

$$ \begin{pmatrix} ct \\ x \\ y \\z \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} \gamma & \gamma \beta & 0 & 0 \\ \gamma \beta & \gamma & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} ct' \\ x' \\ y' \\z' \end{pmatrix}$$

Let $$\gamma \equiv \cosh \xi \geqslant 1$$ and then since $\cosh^2 \xi - \sinh^2 \xi =1$: $$ \gamma \beta = \sinh \xi$$

The Lorentz transformations are analogous to a hyperbolic rotation between coordinate frames.

$$ \begin{pmatrix} ct \\ x \\ y \\z \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} \cosh \xi & \sinh \xi & 0 & 0 \\ \sinh \xi & \cosh \xi & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} ct' \\ x' \\ y' \\z' \end{pmatrix}$$Relativistic Momentum and Energy

Regular Momentum

Momentum vs Velocity

Relativistic Momentum

Relativistic Momentum vs Velocity

Energy

\begin{equation} K = \int_{x_i}^{x_f} F dx = \int_{x_i}^{x_f} \frac{dp}{dt} dx = \int_{p_i}^{p_f} \frac{dx}{dt} dp = \int_{p_i}^{p_f} v \;dp \end{equation}Integrate by parts: \begin{equation} K = p_f v_f - \int_0^{v_f} p dv \end{equation} \begin{equation} K = \frac{m v_f^2}{\sqrt{1-\frac{v_f^2}{c^2}}} - \int_0^{v_f} \frac{m v}{\sqrt{1-\frac{v^2}{c^2}}} dv \end{equation}

\begin{equation} K = \frac{m v_f^2} {\sqrt{1-\frac{v_f^2}{c^2}}} + mc^2 \left( \sqrt{1-\frac{v_f^2} {c^2}} -1\right) \end{equation}

Simplify: \begin{align} K = & mc^2 \left( \frac{1}{\sqrt{1-\frac{v_f^2} {c^2} }} -1 \right) \\ = & m c^2 (\gamma - 1) \end{align}

This terms depends on velocity: $$m c^2 \gamma$$ While this term does not: $$m c^2$$

Rest Energy

\begin{equation} E_{\textrm{rest}} = mc^2 \end{equation}

Nope, no, and still no.

Maybe, but still no.

"Due to the nature of light and energy, it’s impossible to reach the speed of light, nearly 300,000 kilometers per second. It would take an infinite amount of energy. The fastest any human-made object has traveled is only about 0.06 percent of that speed. At that rate, it would take about 6,600 years to reach the nearest exoplanet, Proxima Centauri b, 4.24 light-years away."

"A spacecraft traveling at one-tenth of the speed of light could shave the trip down to a quick 40 years. Future engineers could use nuclear power to achieve that, says Scott Bailey, an engineer at Virginia Tech. But developing that technology could take thousands of years."

General Relativity

Totally not science fiction, now.

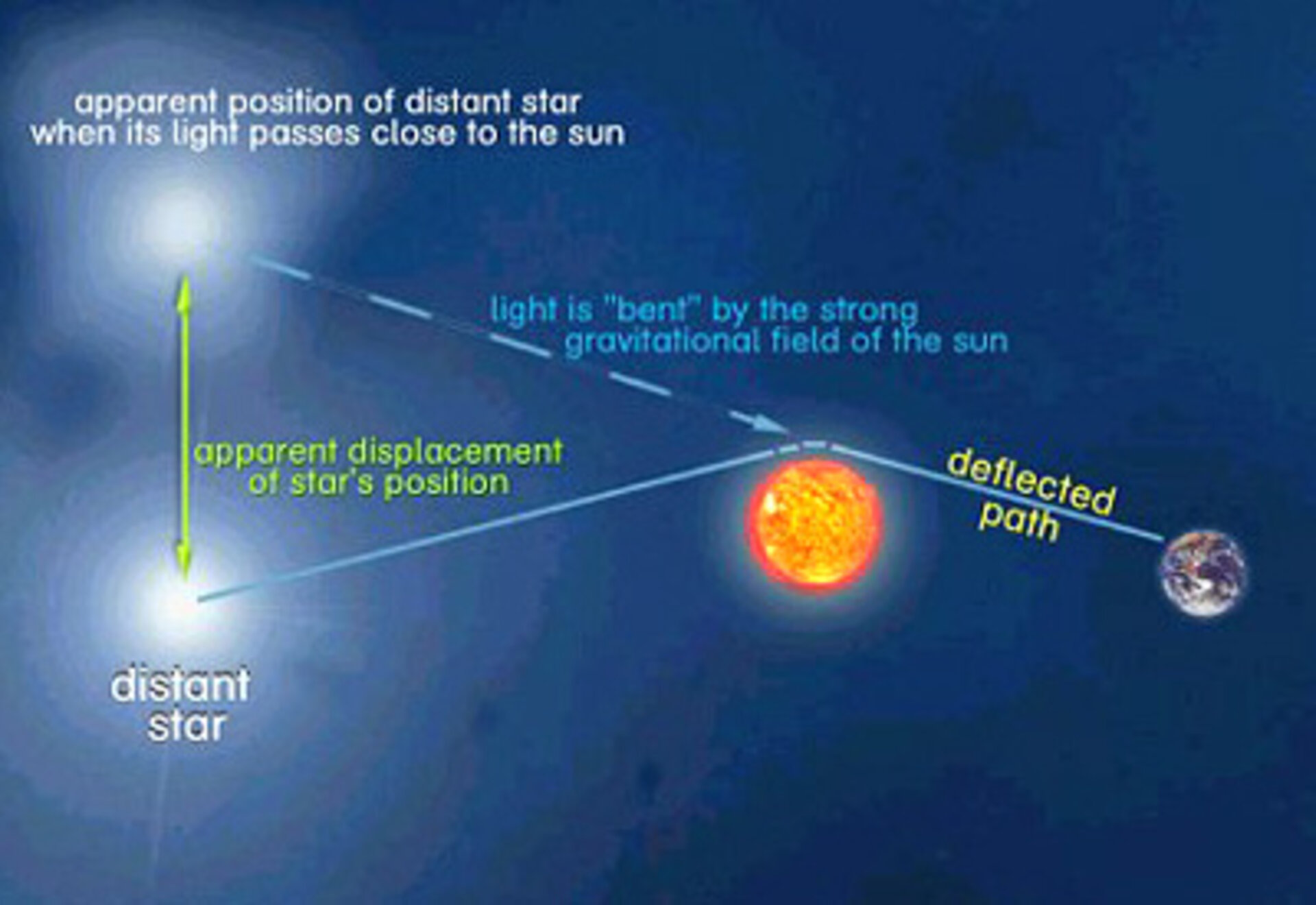

The 29 May 1919 solar eclipse

Bending of Starlight during eclipse.

ESA

Lensing

https://webbtelescope.org/contents/media/images/2022/035/01G7DCWB7137MYJ05CSH1Q5Z1Z